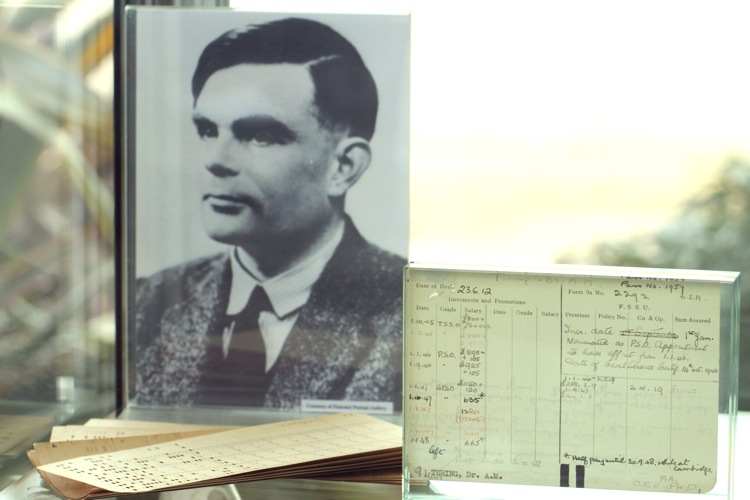

My second meeting in London was at the U.K. National Physical Laboratory in Teddington. Thanks to a display in the lobby, I learned that Alan Turing worked there!

Turing is considered by many as the father of Computer Science. He invented the concepts of a stored program computer in the mid-1930's. He is also famous for playing a key role at Bletchley Park during WWII in breaking the codes used by the German military. I read his biography in my high school years.

Since this meeting wrapped up early, we had some free time on Friday. I found that Bletchley Park was not too far away (65 miles). We debated if we could get there and still have time to look around. By train would take 2 hours and was more expensive than expected. In a stroke of bravado, Matt decided he could handle driving on the wrong side of the road so we rented a car for the day.

Entrance to the museum where most exhibits are.

The Bletchley Park mansion. The estate was owned by a wealthy family before it was acquired by the U.K. government to house the code breakers. It is a mish-mash of architectural styles due to the tastes of its previous owner.

The story of code breaking at Bletchley Park focuses almost entirely on the Enigma machine. This machine, looking somewhat like a typewriter in a box, was used to encrypt and decrypt messages that would be transmitted via radio. It was invented in the 1930's and originally marketed to businesses, such as banks. It wasn't adopted much by business, but the German military purchased some 70,000 units.

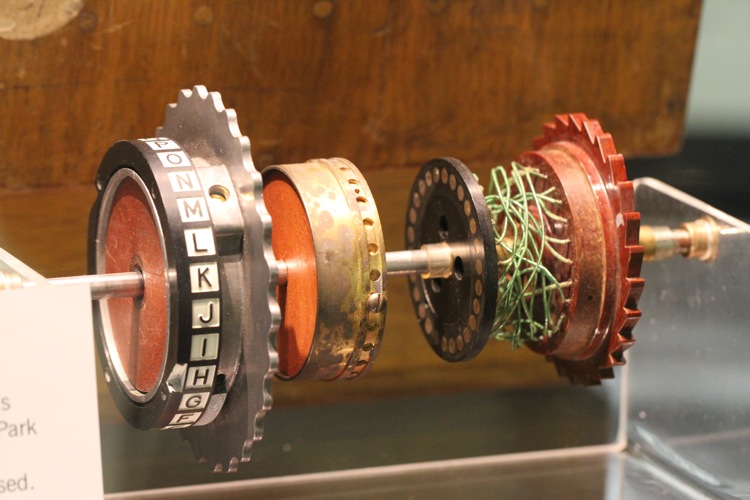

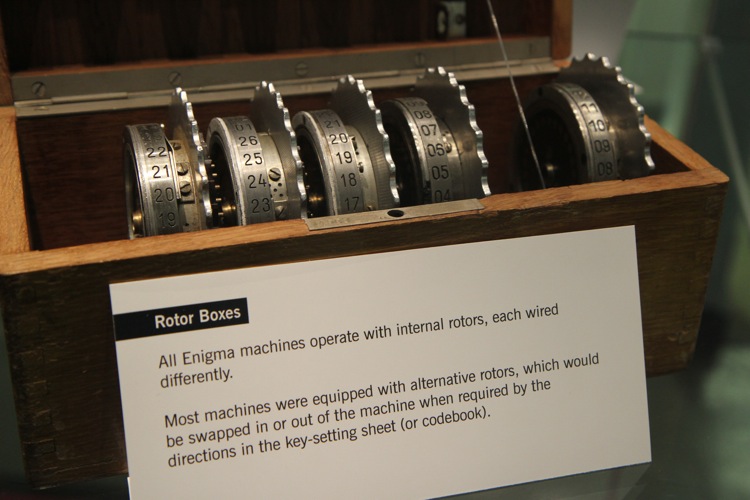

An Enigma machine has a keyboard where the message is typed, a "plugboard" (covered by the front of the box, a number of "rotors," and a set of lamps arranged much like the keyboard. When a key is depressed it causes one of the lamps to light up and one of the rotors to turn. The encryption happens because the electric signals between the keyboard and lamps are scrambled by the plugboard and the rotors.

There are wires inside each rotor that accomplish the scrambling. In order to break the code, they had to figure out how they were wired inside, without being able to take it apart or even see one. Sometimes Enigma boxes were recovered from captured submarines, so that certainly helped.

Some Enigma's had 3 rotors and some had 4. When encoding (and decoding) a message, the operator set the rotors to a specific starting position. The starting position changed each day. So in order to break the codes they also had to determine these starting positions. When the code was broken they could then read all the messages for that day.

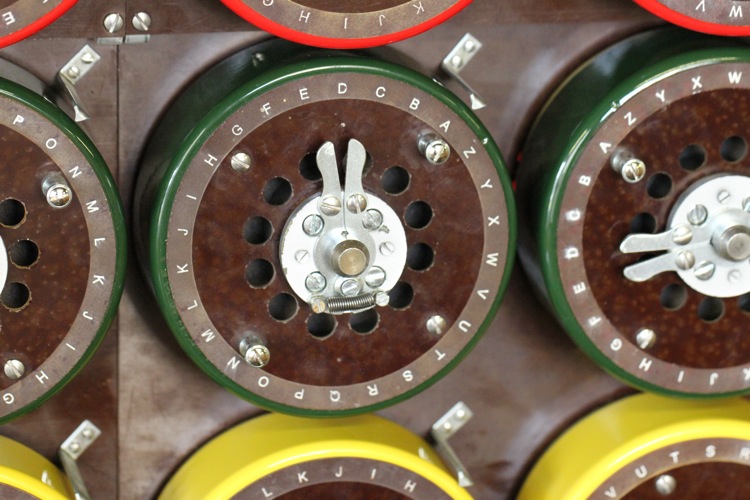

This pictures shows two reconstructed bombe machines, which Turing was instrumental in developing. The originals were destroyed after the war out of fear. One side of the bombe has an array of color-coded discs and the other side consists of long red cables (corresponding to the Engima's plugboard). This photo was taken in Hut 11, which at the time, housed 6 bombe machines. The walls and ceiling are two feet of concrete, designed to be bomb-proof. There were no windows then, and the hut became very hot and probably smelled like oil.

The bombes were designed to crank through potential rotor settings until they found one that might decode the message. Note that the Enigmas generally didn't have numbers on their keyboards, only letters. This fact was useful in breaking the codes because numbers were spelled out, and therefore often repeated and easier to identify.

The code breakers gave different color names to different codes used by the Germans. These may have been different Enigma machines or different protocols and settings. I'm not sure if these colored bombe rotors correspond to those different codes or not. In the reconstructed bombe machines, all rows have the same color.

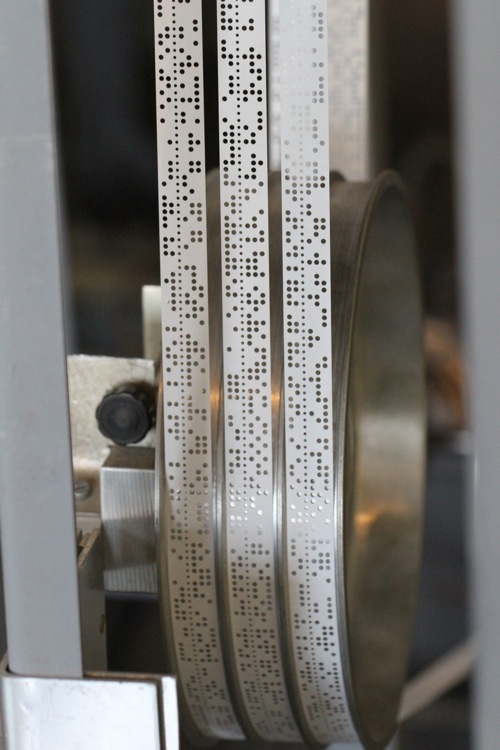

The Germans also used an even more sophisticated encryption machine named Lorenz. In order to crack this, the code breakers built a semi-programmable computer, known as Colossus. The original Colossus was also destroyed, but has been reconstructed at Bletchley Park. This picture shows the paper punch tapes containing encrypted messages being processed by Colossus.

Above is Alan Turning's office in Hut 8. Given the state of decay of most things at Bletchley Park it is unlikely any of these items were actually used by Turing.

Above is a recreation of a "Y" station where German radio transmissions were intercepted and recorded. These were not located at Bletchley Park. For some time the encrypted messages were written on paper and couriered to Bletchley. Later they installed teleprinters between the sites.

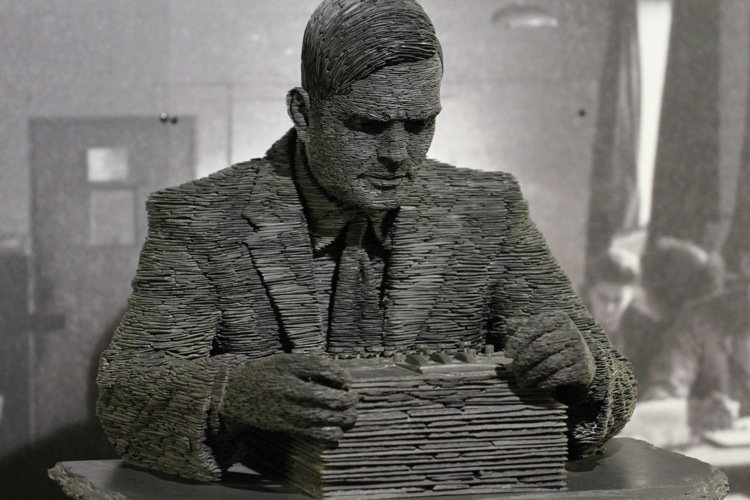

This statue of Alan Turing with an Enigma machine (by Stephen Kettle) sits in the basement of the Block B museum and seems to be made of numerous flat stones.